RAM, Your Memory

TIP

I have a grand memory for forgetting.

– Robert Louis Stevenson, Scottish novelist

RAM

As you know, your memory is a limited resource.

In the ’80s, an average computer had 64K of memory. This amount of memory might seem like a small storage capacity, but it can accomplish amazing things, from complex calculations to advanced spreadsheets and games. The key was to optimize the use.

As available memory increased, applications began to utilize it excessively. Today’s average professional computer has 32 GB of memory, 500,000 times the available memory in the 1980s. Are applications now half a million times better in terms of quality, speed, and power?

You might argue that memory has improved dramatically, and processors are much more powerful. But that is precisely the critical point. With more resources, we require increasingly more memory to perform simple tasks. We are not optimizing memory; instead, we are simply taking advantage of the memory increase to disregard efficient usage.

Our brain has the same problem. We now have access to a tremendous amount of information. Still, instead of optimizing our memory, we systematically use brute force to insert all that information into our memory. Until the end of the last century, access to information was very restricted compared to today, but we still managed to make it work. Nowadays, we still cannot store all that massive amount of information in our memory, but we can access the essential information we need in almost no time.

Making another analogy, we can use our memory as an index page that doesn’t contain the information but knows where to find it. Does it make any sense to learn something and keep it in our memory when the effort to find that information in any repository is almost nonexistent and free?

To give you some data, think about the following:

| Information transmission rates of the senses | |

| sensory system | bits per second |

| eyes | 10,000,000 |

| skin | 1,000,000 |

| ears | 100,000 |

| smell | 100,000 |

| taste | 1,000 |

Britannica, information theory in Applications of information theory

Now, imagine if we had to store all that information continuously, it would be chaos. Our brain is capable of deciding which information should be stored and processed, and which shouldn’t. That said, don’t fight the framework and mimic it.

The first “Apps” we will learn to install in our system will be memory-optimizing.

We can acquire a few techniques and concepts, learn to use them optimally, and keep our resources for what’s important or necessary.

How Our Memory Works

People commonly believe that our memory works like a hard drive. When we decide to store something in our memory, we insert it into our brain through any of our senses (vision, hearing, touch, smell, or taste), and our memory finds a place to store it. When we need to recover that information, we retrieve it from where we stored it.

Why do we have some incomplete or inaccurate memories after years? Does our mental repository get corrupted with time?

Why are there some memories we remember so clearly and others we can’t remember? Does our mental repository contain some Class A folders and some Class B folders? Why do we fill the gaps with invented information?

Why can some people remember some information better than others? Does our mental repository have preferences for some info?

Although it is still unclear how the brain works, we know some things that can help us remember what we want. People who become blind over time often forget how to recognize shapes and colors, but they dramatically improve their sense of smell and auditory memory. This effect demonstrates two concepts: our memory needs refreshment, and when there is a deficit in any memory, it is replaced and reinforced in other types of memory.

An excellent example is a situation we all experienced at some point. Your first day in a new job. It usually starts with a tour around the office, during which you are introduced to many people. Your cicerone will introduce you to everyone you meet on that tour. What happens at the end of the day? You can remember three or four names. Imagine your new boss giving you a list of one hundred names and photographs of people after that first day. All the names you’ve been told are on the list, and all the people you’ve met are in the photographs. If you are asked to find your coworkers’ names in the list and select their pictures, which kind of information do you think you’ll be more capable of identifying? I bet that you can recognize more faces than names. The reason is that an image contains much more connected information than a name, which is just a simple piece of information that can’t be connected to anything else. This fact demonstrates how our visual memory is more efficient than our auditory memory. The cause for this is the kind of animals we have evolved to be.

One hundred thousand years ago, we needed our memory to remember things such as which fruits we could eat and which we couldn’t, what kinds of animals were dangerous and not a threat, where the nearest water source was, and which sounds meant danger, among other things. Our memory was perfect for remembering shapes, colors, textures, and these kinds of things, but we never needed to know how many fruits were in a tree, how many liters had a lake, or how we felt when sitting under that tree; those are tools we invented for our convenience, they were not life-saving concepts, so they were not empowered and transferred to subsequent generations.

Our information was transmitted by instinct, much like the irrational fear some people have of spiders or snakes, and through oral traditions, such as tales and songs, which were passed on to others. None of that information was related to numbers, operations, or abstract concepts like possession or money. We needed to invent those concepts and add a tool to transmit them. The tool we invented was scripture.

The evolution we have experienced over the last 5,000 years is insignificant in the context of human existence; therefore, we haven’t been able to incorporate that kind of memory into our brains.

As you can deduce from this, and probably from your own experience, we have different kinds of memories, which is another advantage over a computer’s simple memory. We need to learn to utilize the type of memory we have, rather than trying to use a tool we don’t have. The best option is not to fight the framework but to learn how to use it optimally.

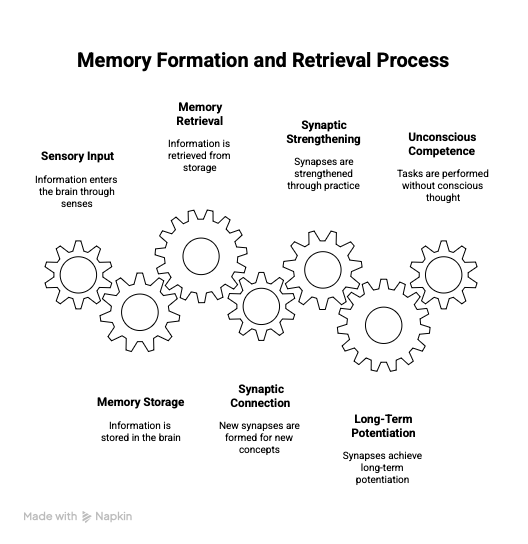

The theory of the synaptic connection is the most widely accepted theory of how our memory works. This book is not a science book; it won’t delve into this theory in more detail than necessary to explain how it works.

A synapse is a structure that permits a neuron to communicate (pass an electrical or chemical signal) to another neuron. When learning a new concept, we create new synapses, and that is the memory itself. As we reinforce these concepts through practice, reading, or listening multiple times, this produces synaptic strengthening, which is what is known as long-term potentiation. Similarly, if we don’t reiterate that concept’s insertion, the synapse becomes weaker with time until it disappears.

This methodology is what I was referring to as brute force. It is sometimes necessary to fix that knowledge in our brains. Martial arts utilize this technique to create what is called muscle memory. So do musicians by practicing once, and then again, and again, the same music sheet. If we practice enough, we reach unconscious competence. This effect occurs when we perform tasks without needing to think about them. It happens when we drive, walk, or even eat. We don’t need to follow each step. We need to perform any of those actions. Furthermore, we do it.

Of course, we can’t abuse this technique because it requires a lot of time and demands that you focus on specific knowledge; it is not a silver bullet.

Another great advantage is that we can create different types of so-called connections. As commented above, we can connect two concepts by how they look, smell, taste, or feel; that is how we make stronger links to recover what we need from our memory.

Your Memory Enemies

In 1997, Christopher Chabris and Daniel Simons, two psychologists, designed an experiment consisting of a ten-minute video showing two groups of people passing a ball to one another. They selected a group of students and asked them to count the number of passes one of the groups did. Because they were so focused on counting them, they failed to notice something out of context. In the middle of the video, a woman dressed as a gorilla walked through the scene. She stops in the middle of the stage to beat her chest. That gorilla stays in the background for a few seconds, but none of the viewers notice it.

Chabris and Simons won the Ig Nobel Prize because of the results of the work derived from that experiment, and in 2010, they published a book called The Invisible Gorilla and Other Ways Our Intuition Deceives Us

In their web overview, they write.

TIP

Reading this book will make you less sure of yourself, and that’s good. In The Invisible Gorilla, we present a diverse range of stories and counterintuitive scientific findings to reveal a crucial truth: Our minds don’t function the way we think they do. We believe we see ourselves and the world as they are, but we’re missing a great deal.

We frequently rely too much on our perceptions, which often stem from previous experiences that, without even noticing, take us back to similar situations, causing a series of mistakes that lead to errors because no two situations are ever identical. Furthermore, we could avoid those situations with more awareness. The book states that we are all victims of six illusions.

Illusion of Attention

In the Gorilla video, it becomes evident that we are too confident in our ability to pay attention. When we focus on something, we usually miss everything happening around us. We also can’t see those things. We don’t even know they exist. An undeniable situation occurs when trying to follow GPS directions while driving; we focus on reaching our destination, and nothing around us catches our attention except the GPS indications. Have you ever heard the expression, “Sometimes, we can’t see the forest for the trees”? It clearly expresses the inability to see the whole situation because your focus is on the details.

For this reason, when reviewing code, it is essential to have a global view of the code and not focus solely on looking for specific problems, which can distract us from identifying the rest of the issues. If you are looking for something specific, it won’t let you see anything but what you want to see.

Illusion of Memory

We are all too confident in our memory. When we recall the past, we often believe things are as we remember them, but that’s not always the case. Have you ever experienced the feeling that a room or a house was smaller than how you remember it? Goebbels, the architect of the Nazi propaganda, said.

TIP

If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it

And this, somehow, happens in our memory, too. If you create fiction about how you’d like something to have occurred, at some point, your memory won’t be able to notice which was the real version and which is the idealized one, so you will create a fake record.

Have you ever been somewhere you hadn’t visited in years that you remember from your childhood? When we are kids, everything seems to be bigger; we compare it with ourselves, and that record grows with us as we grow. You “remembered it bigger than it is,” which is another way to see the illusion of memory.

Illusion of Confidence

Confidence in what you know or believe is no guarantee that you are right. Many witnesses in court show strong confidence in what they saw, but there is no correspondence with the evidence that is proven. They are not lying; they are too confident about their memory. Therefore, we should always be open to considering other options or contrasting our beliefs. It doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be convinced, but you should consider the possibilities.

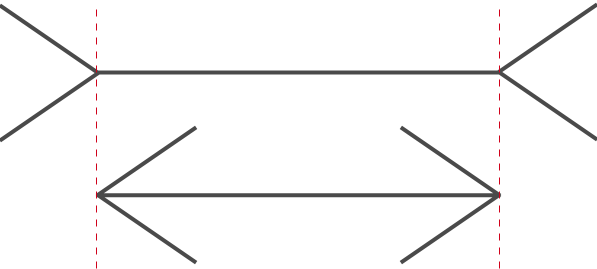

Look at the picture representing a Müller-Lyer illusion. You might have seen it before, but even though you know that both lines are the same length, your eyes keep telling you that the top line is longer than the bottom line. In a nutshell, this effect is what the illusion of confidence produces. Your senses and perceptions provide you with some information that you want to follow, but that doesn’t match reality.

Illusion of Knowledge

The illusion of knowledge has often been defined as the opposite of the impostor syndrome. When someone has a reasonable level of expertise in a particular area, the tendency is to overestimate their knowledge in that area. This situation leads us to fill the gaps with our perceptions instead of recognizing a lack of knowledge. It is not a voluntary act but a consequence of our experiences. Usually, in simple situations, we can overcome problems by learning or improvising as we progress in solving the problem, but that is rarely the case for complex conditions.

Experience shows that, in case of doubt, admit ignorance. That doesn’t present you as less expert in any area, but as a cautious and humble professional who wants to leave as few situations as possible to chance.

Illusion of Cause

Experience is vital for us to solve problems. This experience helps us identify a situation we faced in the past and apply the solution that worked in that situation. It allows us not to start from scratch whenever we need to solve a problem.

Another extraordinary skill that our millions of years of evolution have endowed us with is the ability to extract patterns from abstract situations, which is great as a survival tool but is not always ideal in our modern world. Occam’s razor states, “The simplest explanation is usually the best.” For example, if you find a ten-dollar bill in your jacket, it is more likely that you left it there than that the tooth fairy left it there.

If we combine experience with pattern recognition, we discover causes that are not the actual ones for the problem we are solving. As stated many times in this chapter, memory is a valuable tool, but it sometimes needs moderation. We can fall into the illusion of finding the cause based on our memory, but this is often untrue. An excellent example of this situation was the Black Death in Europe during the 14th century. People saw the cause of the plague as God’s punishment or “bad airs”; nobody realized that the problem was the killing of most of the cats in the cities, which favored the growth of the rat population, which served as hosts for the fleas that transmitted the plague.

To solve this problem, we have some tools, such as root cause analysis, which helps us find the cause based on facts, not perceptions.

Illusion of Potential

You probably know that myth about our brain potential that states that we are only using 10% of it. There is no evidence or demonstration to support this theory; it is likely to originate from some statements by famous scientists. However, even if it is not valid, the collective imagination deeply ingrains this concept into the culture. Trending ideas, such as “Everything is possible if you want it enough,” are the root cause of our inability to understand where our limits lie.

We have limited potential, and we need to be conscious. We can’t be experts in something we want just with practice and time; there are other aspects, such as natural-born skills. Being an expert in one thing doesn’t necessarily make you an expert in different skills. It occurs when someone believes that being a great technical leader automatically makes you a great people manager, or that being a company founder automatically makes you a good CEO.

Recognizing our limitations is crucial, and we must rely on others to maximize the effectiveness of our actions. There is no such thing as the “one-man band”; that is the best way to end up being an apprentice of all trades, master of none.

Enjoy the process

When I was a kid, I had a great teacher, one of those old-school types, who taught us in a very unconventional way. He used to create songs that taught us the lessons we needed to learn, and we would sing them together during school. We even made some modifications to the songs to improve their sound quality. It was a fantastic experience, and it helped me learn with almost no effort.

Later, as a teenager, as most of us probably know, I was seduced by music, mainly English and Spanish. It was easy for me to learn songs, even if I didn’t understand the lyrics or invent them sometimes, by constantly repeating the exact text.

I often wonder why it was so easy for me and many others to learn a song’s lyrics and retain them in my memory years later. I still remember the songs I learned at school about history, mathematics, language, and other subjects.

It opened a whole line of investigation for me.

I discovered that, for religious people, it happens the same way with the prayers; they learn them and become part of their memory repository forever.

On one side, repetition is vital here. You repeat the same concepts once and again, reinforcing the synaptic connections between your neurons, which makes it, so to speak, “strongly engraved,” but there was another part, which is the ease of fixing that content in that way.

Is there anything special about music that enables us to acquire information? Is it the music or the rhymes that make it easy? Maybe it’s just that we give a layer of sugar on top of what we want to learn. It could be the same effect I used with my daughters to help them eat vegetables. Raw vegetables were never accepted by my daughters, nor were cooked ones. So I tried to create drawings and figures with them, using tomatoes as eyes, carrots as the nose, and so on over a base of vegetable cream. I also bought dishes with a drawing on the base, so I encouraged them to discover which drawing was there as soon as possible.

The result is that, since it is not their favorite food, they can overlook the unpleasant part of eating vegetables and focus on the enjoyable aspect of the process.

This is the conclusion I’ve found so far. I’ll continue investigating to find an excellent system that makes it easier, but for now, the conclusion is that preparation is critical. Spend some time preparing your learning path by removing the most challenging parts, enhancing the good ones, removing obstacles to focus on learning, and creating an exciting and joyful learning experience.

Select What to Add

Not everything you need to use should be committed to memory.

Following the principle of memory limitation, you should be selective about what you store in it.

The first filter to use is to discard any well-documented information or documents that you don’t need to use daily. It doesn’t mean you should remember information that isn’t well-documented. In this case, you should create that documentation, but that’s part of another chapter of the book.

We create documentation to consult. Create or use a sound documentation system, and you will have unlimited external memory.

Don’t memorize APIs, specifications, or specific values. This information is continuously evolving and changing, and you don’t want to keep obsolete or useless information in your memory. The effort needed to memorize is enormous. Use it only on those things that are worth it.

Avoid memorizing any procedure or method that doesn’t add value or that you can automate. In further chapters, you will see that you should automate anything that you can automate. If there is a tool that can do it for you, you shouldn’t be doing it. Clear examples include setting up a new project, data migration, document formatting, sorting and classifying documents by type, and configuring a development environment, among others. You can quickly automate this procedure with many scripting languages or tools. Why should you keep in mind how to do it? Don’t keep in your mind what you are not going to use often or has a quick way to recover

Method of Loci

This method is very ancient, dating back to Ancient Greece. The first description of this method is from Saint Augustine in his Confessions, where he likens it to a warehouse where one stores memories. It is also called the Memory Palace, Memory Journey, or Mind Palace.

The Eight-time World Memory Champion Dominique O’Brien popularized it. He uses this method, among others, to memorize two unsorted decks of cards just by seeing them once, and then he can tell which cards are in sequence.

The American Physiological Society published a study about this methodology. For this study, the APS identified 28 students from diverse areas. Among other results, the study showed that most students, 92.9%, could recall facts better after learning them with the Method of Loci.

However, the most impressive aspect of this method is how easily it can be learned, applied, and benefited from.

Before humans developed the ability to write, they transferred information from generation to generation. It happened when, in middle age, illiteracy was widespread. And people did it by telling stories. Stories, such as tales or songs, are easy to understand and remember. Our brain is good at remembering stories because we create relations and use our imagination to strengthen those synapses.

In essence, the method of loci consists of linking a place you know very well with the information you need to remember. The basis of it is two principles:

- Connection Principle - It is much easier to keep something in memory when you connect elements you already know with concepts you are trying to learn.

- Von Restorff Effect - Also known as the isolation effect, it states that among multiple homogeneous stimuli presented, the stimulus that differs from the rest is more likely to be remembered.

These two principles suggest that you utilize what you know and imagine unusual things to refine your mind’s concepts. In some way, you are talking with your brain in its language.

The place

All stories happen in a specific place. Choose a site that is familiar to you. Although it is not strictly necessary, it will always be more comfortable as you don’t need to add more information to the process than is purely required. It can be a room, a field, a town, a street, or even your working desktop. Anything will work.

The chronological order

Stories always happen in a particular order. In this case, you must define and follow a path to create it.

The characters and objects

Characters and objects are the accurate content and the actual power of the method. You need to create or add any character or item that you can relate to to build a mnemonic image, thereby establishing a connection between what you need to remember and the object or character you have created.

To increase the effect, ensure the scenes are as absurd as possible; this potentiates the Von Restorff Effect. Participate in the story. If you are a movie character, that will be even more familiar to you, thereby increasing the connection principle.

If a word is too complicated or not easy to fit in, decompose it or try to rename it in some way that makes it easier for you.

TIP

The most crucial concept in this method is to imagine all the story elements with as much detail as possible. Your imagination is one of the most powerful tools you have.

As always, the best way to learn is by example, so let’s apply the method by preparing a speech.

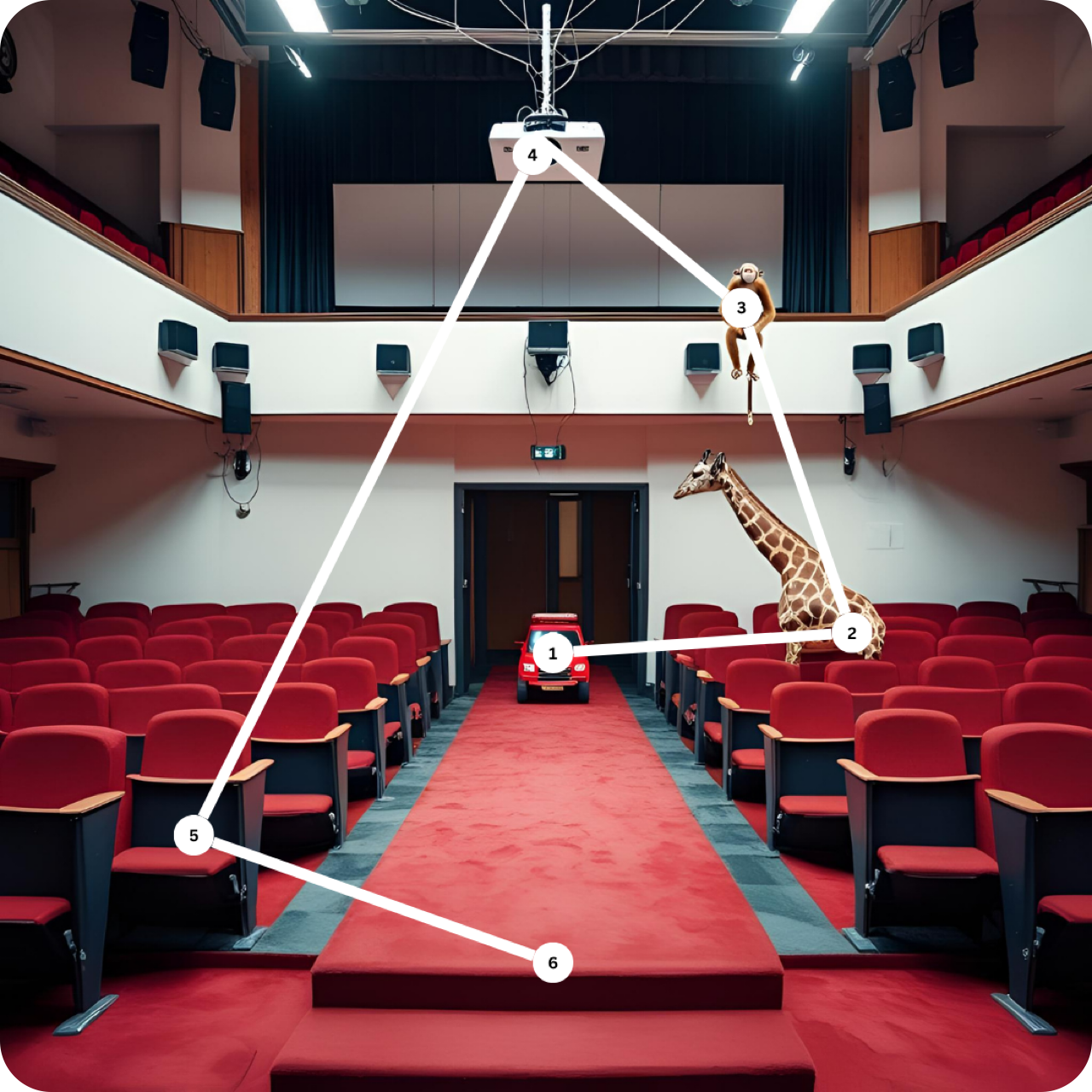

Method of Loci Example

Method of Loci Example

Imagine that you need to deliver a talk next week. The biggest fear is forgetting any of the topics you need to discuss. So we’ll apply the method here.

You need to discuss how we entered the market, the company’s growth, pending issues to resolve, the focus for next year, our market position, and extend thanks to the audience.

Let’s add some unusual elements to potentiate the Von Restorff Effect, such as a truck, a giraffe, and a monkey hanging on.

Now let’s create a path to move from one element to the other, for example this one.

With all elements in place, we can create a tale to remember all the topics.

First of all, we recall the truck entering the auditorium, which represents how the company disrupted the current market. Next, you move on to the giraffe, whose long neck reminds you how the company grew this last year, so it’s time to talk about growth. Number three is the monkey hanging, which represents things that are still pending resolution. The fourth stop is the projector, which means the focus. Let’s discuss priorities for next year. Next, we move to the first seat row, where you will explain how we position ourselves as the market leader. Finally, you move to the red carpet, where you will imagine your people parading, and you will thank them for their efforts.

Exercise 2.1: Create a scenario with a list of people you need to thank for their efforts. To do this, find an alternative location and associate each person with a step on the path.

Takeovers

TIP

Your memory is a limited resource.

Practice reinforces our synaptic connections.

We frequently rely too much on perceptions.

If you are looking for something specific, it won’t let you see anything but what you are looking for.

What you remember does not necessarily reflect reality.

Your senses and perceptions sometimes fail to reveal reality.

Being humble will help you be open to new learnings and improvements.

Look for the real cause of the problem; don’t rely solely on previous experiences.

Be aware of your limitations and seek assistance from others to help you reach your full potential.

Not everything you need to use should be committed to memory.

Acquire new skills to enhance your memory and cognitive abilities.