Task Manager

TIP

To do two things at once is to do neither.

–Publilius Syrus, Roman philosopher

Multitasking

Current CPUs are multicore, which means they are a set of CPUs working together, pretending to be one to you. This fact, in conjunction with our perception of the CPU as the “brain” of the computer, leads us to find some similarities between the CPU and our human brain. Still, the reality is that in this aspect, we are closer to the old Intel 8086 than to the actual CPUs, which are capable of performing tasks in parallel, something we cannot do.

We have the wrong impression that we can do many things simultaneously, multitasking. The reality is that we are only pretending that we have that skill. When I think about it, I soon realize I can’t even move the spoon in circles to mix the sugar with the coffee while reading; I know that I usually stop moving the spoon to focus on reading.

The reason for that is simple. When we focus on one task, all our resources are focused on performing that task. We often have the wrong impression that we can do more than one thing simultaneously, but that is just a perception, as we’ll soon see. We are just task-switching. I will elaborate more on this concept in this chapter.

We can’t multitask

The best way to understand what I’m talking about is by experiencing it firsthand. There is a straightforward exercise you can do to check the myth of multitasking by yourself.

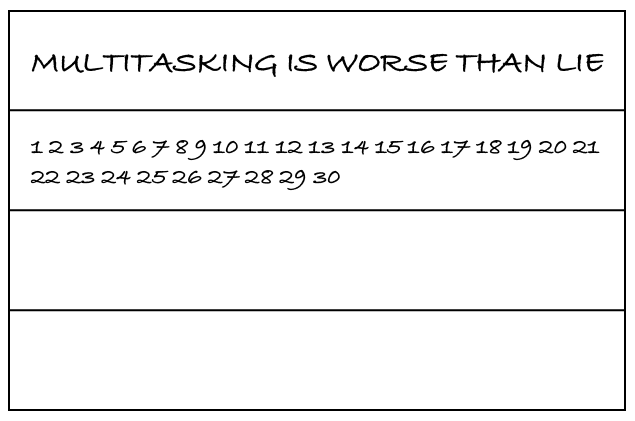

Exercise 1.1: Multitasking is worse than a lie.

I found this exercise in the book The Myth of Multitasking: How Doing It All Gets Nothing Done by Dave Crenshaw, which I recommend you read. You will find all book references at the end of the book in the bibliography.

This exercise poses no difficulty, but it highlights how often we overlook the impact of pretending to multitask.

Start with a blank sheet of paper and draw this table.

The exercise has two parts, and you will need a chronograph; you must check how long each section of this exercise takes.

In the first part of the exercise, you need to use the two rows at the top. To complete this first part, you will write the sentence :

Multitasking is worse than lying

In the second row, you will write the sequence of the first 30 numbers.

This image shows how the first two rows should look at the end of the exercise’s first part.

For each letter you write in row one, you will write a number in row two. The sequence is M-1, u-2, l-3, and so on.

Remember to control the time you spend on this exercise. The key to this exercise is the elapsed time difference. Once you finish this first part, annotate how long it took to complete this part of the exercise next to the first two rows.

WARNING

Wait to continue until you finish the first part of the exercise.

Did you finish the first part? Did you annotate the time it took? Awesome. Now, we can start with the second part of the exercise.

You need to use the two rows at the bottom for this second part.

You also need to control the time in this part to compare it with the first part.

The second part of the exercise consists of writing the same sentence and numbers sequence you did in the previous section, this time in the bottom rows. In this case, you will write first the sentence, “Multitasking is worse than a lie,” and once you have finished, you will note the sequence “1 2 3 4 5 6 7 … 28 29 30”.

If it’s clear, go for it!

WARNING

Only continue once you finish the second part of the exercise.

Now that you have finished, you can compare the results. If the results are similar to those of the individuals I asked to do the exercise for me, the time spent in the first part almost doubles the time invested in the second part. Isn’t it awesome? Almost double.

Task Switching

This exercise illustrates how two seemingly straightforward yet distinct tasks can have a significant impact when performed simultaneously.

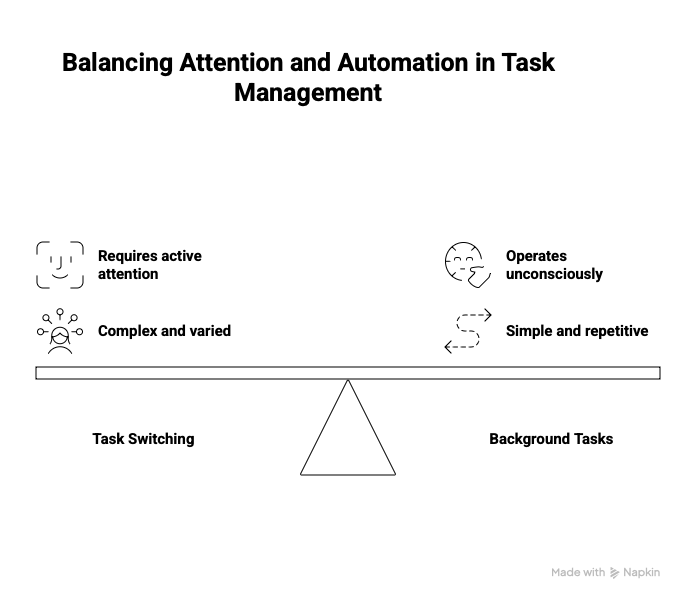

The fact that the first task contains letters and the second task includes numbers, changes your mind context. I said it simultaneously, but you can see that you are not multitasking; you are just switching tasks. You can’t multitask because you have only one processor, your brain.

That’s what we call Task switching.

Imagine what truly complex tasks can do if two simple tasks have this incredible effect.

You might argue that there are cases where you can do two or more things simultaneously, such as driving and speaking with someone in the car; however, we are considering different situations. In the case of driving, your car is a “background task.” It does not require your attention because you have reached the “Unconscious competence” level (we’ll discuss it in future chapters). It is a simple task for you and does not require the level of attention that you might need to write an email or review code. In the “Load New Content” section, we explain that you can install two types of skills: Applications and Daemons.

Imagine doing anything else when you drove your car for the first time. At that time, it was a complicated task, but you did it so often that you internalized it, making it a background task. What I call Background Tasks are those tasks we internalize so much that we can perform them without thinking. Some great examples of that are what happens in martial arts and music.

Think about each movement you must make in martial arts to react to your opponent’s move. If you analyze and prepare for your move, you’re done. Your opponent will catch you. Your reaction needs to be almost automatic. To reach that efficiency level, you must practice the movement thousands of times until you create muscle memory. We develop muscle memory after repeatedly performing the same action, so you react to the trigger more efficiently as you practice. Initially, you are clumsy and slow on the technique, but as you become more used to it, you perfect it until you don’t need to think to act.

The same happens with musicians; they don’t think every time they need to play a composition and place their fingers; they know it because of constant practice. When they think about a Do, their hands move there. When they need to play the next strophe, their hands move note after note on the instrument and play the expected sound. That, again, comes after an immeasurable number of hours repeating the same movements.

Typing is another excellent example of a background task; after some time typing, you don’t need to look for the key that contains an “a” to type it; your fingers go there automatically.

Those are background tasks, which is why you can’t consider them in the same context as tasks we do a few times a week, each time differently.

Usually, complex tasks can not be background tasks, but background tasks will help you, as we’ll see, a lot in performing complex tasks.

Divide your time into slices

TIP

The average American worker has fifty interruptions a day, of which seventy percent have nothing to do with work.

–W. Edwards Deming, American engineer, statistician, professor, author, lecturer, and management consultant.

A study from the University of California, Irvine found that it takes 23 minutes and 15 seconds to get back to a task after an interruption on average. An interruption is not just anyone walking up to you to ask you something. Interruptions include emails, social network notifications, and web surfing unrelated to work, among others. It is not easy to block your whole day to avoid interruptions. It is also unacceptable to create a queue of people waiting to talk with you until you finish your current task. In that same study, Gloria Mark indicated that, on average, a worker is interrupted every 10 minutes and 29 seconds. These interruptions represent around 45 interruptions a day.

Let’s give an example. If we were interrupted only ten times a day, far below reality, how much would we effectively dedicate to being productive? Ten times a day, it would be one interruption every 48 minutes. To make easy calculations, let’s assume we need 20 minutes to get back on track. Also, let’s assume that the interruption takes five minutes of your time.

The first work chunk would be 48 minutes. After that, every 48 minutes, you receive an interruption. That means that for each 48-minute work chunk, you are only productive:

\[48 - 5 - 20 = 23\]That represents 23 productive minutes per work chunk.

Let’s make the day calculation. You have ten work chunks daily, totaling 480 minutes, which is 48 minutes per piece. You are productive for 23 minutes per chunk, which means 230 minutes. Two hundred thirty minutes is three hours and fifty minutes.

WARNING

That represents only 48% of your working time.

Okay, this calculation is a bit misleading and does not fully reflect reality, but you get the idea.

We also have another problem to fix, though. You shouldn’t work for eight hours in a row. It is essential to take regular breaks throughout the day. Just because we are not machines, we need to give our brains some free time from time to time. My experience is that I can maintain focus continuously for a maximum of two hours, which is the typical duration. After two hours, my brain disconnects, and I start thinking about anything but work.

Fortunately, we have a technique that helps us address both problems simultaneously.

This technique is The Pomodoro Technique, a method created by Francesco Cirillo. There are great books about this technique.

In a nutshell, this technique proposes using a timer to break down work into intervals of around twenty minutes in length, at the end of which you take a five-minute break; the duration in minutes can vary, but these are the standard values. After four pomodoro, which we call those intervals, take a more extended break, typically 15 minutes.

As an example, two working hours would be:

| Time | Action |

|---|---|

| 25 minutes | First Pomodoro |

| 5 minutes | First short break |

| 25 minutes | Second Pomodoro |

| 5 minutes | Second short break |

| 25 minutes | Third Pomodoro |

| 5 minutes | Third short Break |

| 25 minutes | Fourth Pomodoro |

| 15 minutes | Long break |

So your working day could be something like:

| Hour | Action |

|---|---|

| 8:00 | First Pomodoro block |

| 10:10 | Second Pomodoro block |

| 12:20 | Lunchtime |

| 13:00 | Third Pomodoro block |

| 15:10 | Fourth Pomodoro block |

| 17:20 | end of the day |

This timetable is an example of how you could organize your day, but you should adapt it to your needs.

These five-minute breaks and fifteen-minute breaks are the times you need to use to attend to these interruptions. You must address two things before you can maximize the result. First, turn off any notification system, put your phone in Not Disturb mode, close your email app (except if the Pomodoro is for email review), and close any instant messaging apps. There is nothing that urgent that can’t wait for twenty minutes, and if there is, people will find a way to let you know. The second thing you need to do is plan the tasks so that you can complete them in twenty minutes or less. That doesn’t mean only working on short tasks, but making it possible to get back on track as soon as possible after the break. Many apps can help you do the Pomodoro technique, but you can also start with your cellphone’s timer.

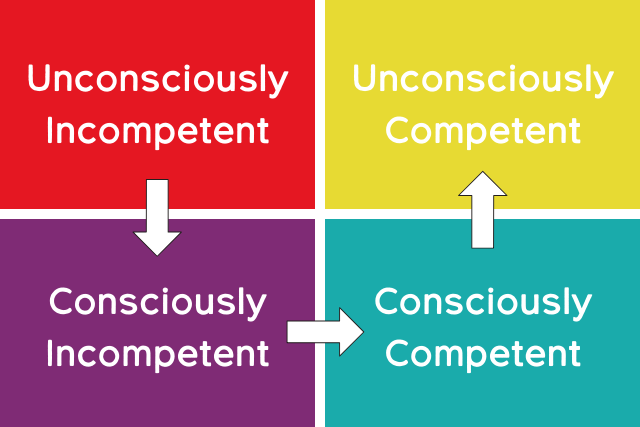

The Four Stages of Competence

To complete this definition, I will introduce a model called “The Four Stages of Competence,” which helps us understand the process of competence acquisition that we undergo when learning any skill. This model appears in the book “Management of Training Programs” published in 1960 by three management professors at the University of New York. These levels define at what stage you can find yourself when acquiring a new skill and guide you to the next step.

Unconscious Incompetence

“You don’t know what you don’t know.”

Imagine a task you need to perform, like bending an iron bar. You’ll try to bend it using brute force because you don’t know that heating the bar will make it much more manageable. It means you are in the unconscious incompetence stage, unaware of a skill that can make it doable.

It is why you should always be open to new options and possibilities. The good news is that this stage marks the beginning of new learning, the moment when you can evaluate different options and choose the best one for your purposes.

Conscious Incompetence

“You know what you don’t know.”

Being aware of what you cannot do, yet knowing there is a way to do it, is the beginning of the journey. As the pleasure you experience when you read a book for the first time, you can experience it only once per skill, and you’ll never have the opportunity to get so excited when learning that specific skill, so enjoy the process. Knowing there is a way to do something, and you don’t need to create it, is an exceptional situation well-defined as “stepping on a giant’s shoulders.” Nobody has created a complex task from scratch; everybody can and should build upon what others have created and take it to the next level.

Conscious Competence

“You know how to do it.”

When you acquire a new skill, everything seems complicated and requires attention. You know how to do it, but it is not something you do automatically. As the saying goes, “The practice makes the master.” The more you practice and use your newly acquired skill, the closer you’ll be to the last stage. Mastering any skill requires experience and repetition. This level marks the stage where you begin the process of mastering.

Unconscious Competence

“You don’t even realize that you know it, but you do it.”

This one is the mastering level. You have reached a level of mastery where you no longer need to think about what to do; it becomes natural and an integral part of your approach. As explained earlier, this is the level required by any professional musician, martial artist, or experienced driver. Once you are at this level, the skill becomes so natural to you that you can no longer see a difficulty or a challenge in any task that requires this skill.

The level of consciousness or unconscious competence you need to acquire will depend on your needs. It makes no sense to become an expert on soldering if your job is to write software. You should know how to do it because you need to fix your keyboard occasionally, which doesn’t require an expert level of skill. In an ideal world, we would be like Neo in The Matrix and become experts by uploading knowledge directly into our brains, but by now, achieving an expert level requires a significant amount of effort, time, and sacrifice. Choose wisely what you invest your time in.

These stages are not always met in all learning processes, as we might find ourselves on some skills more advanced than just in Unconscious Incompetence. However, we will cover most of them in all our learning paths, so take them as a guide for understanding it all. {pagebreak}

Task Execution

TIP

Do or do not. There’s no try.

–Yoda, Jedi Master

The best and only way is to focus on one task, complete it, and then move on to the next. That is why it is essential to have a good task organization and prioritization methodology. It makes no sense to start working on a task when you need to attend to something more urgent and crucial. And that prioritization is what we will see in the following section.

It is not mandatory to fully complete any task you need to perform; you can do part of it and then continue with it later. However, as we’ve seen in the previous exercise, context change has an incredibly high cost for our productivity.

Our “single-core” brain can do amazing things that a nonexistent CPU can. Still, as we’ve seen, multitasking is not one of those. Hence, we need to acquire the required applications (or methodologies in our case) that allow us to maximize our fantastic abilities. Let’s start with.

Collection

Collecting tasks is a continuous activity. We receive inputs throughout the day, and some of these require our attention. These are the tasks we need to collect. The problem arises when we hold the wrong belief that we can contain them all in our privileged minds. As we’ll see in the chapter dedicated to the RAM, this is unlikely to be sustained in terms of time and volume of tasks. As David Allen, creator of the GTD methodology, said, “Our mind is for having ideas, not holding them.”

It is not uncommon for a new task to enter our ecosystem, tempting us to prioritize it and start working on it as soon as possible. It is a significant error for several reasons.

The first is the cost of context switching, which we’ve seen previously; we pay a tremendous price to stop doing what we are doing and start doing another thing.

The second reason is that we don’t know when we will be able to retake the previous task, as we did not evaluate any costs or dependencies associated with the new task.

The third reason is that we had no accurate prioritization of that task, so we could be investing our time in tasks with lower priority than the ones we are currently working on.

For these and other reasons, we must be clear about separating task collection from task execution. To make it possible, the first tool we need to keep in our tool belt is a set of supports that can hold those tasks. In my case, I use my cellphone, a pocket notebook, and an A5 notebook on my desk. But anything you can write on will be a good support.

Any task that comes to mind during a meeting, while commuting, in the shower, while having lunch, or while talking to a teammate, or in any other situation, I write it down in one of those supports, the most handy one. I use a phone and a pocket notebook because, depending on the situation, I sometimes decide not to carry my cell phone with me; even in that case, I can still have ideas or receive requests, and I need to keep them in mind in a place where I can return later.

You must write down these ideas, tasks, questions, and any other information as soon as it arrives. That way, you free your mind from having something sitting there, with a mental trigger reminding you not to forget it, or worse, forgetting it. You will feel that relief instantly.

We’ll call these supports from now on Inboxes.

You can have as many as you think you need, but remember that you have to process them, so if you have too many InBoxes, processing them will become more tedious. The rule of thumb here is to have one InBox per physical context.

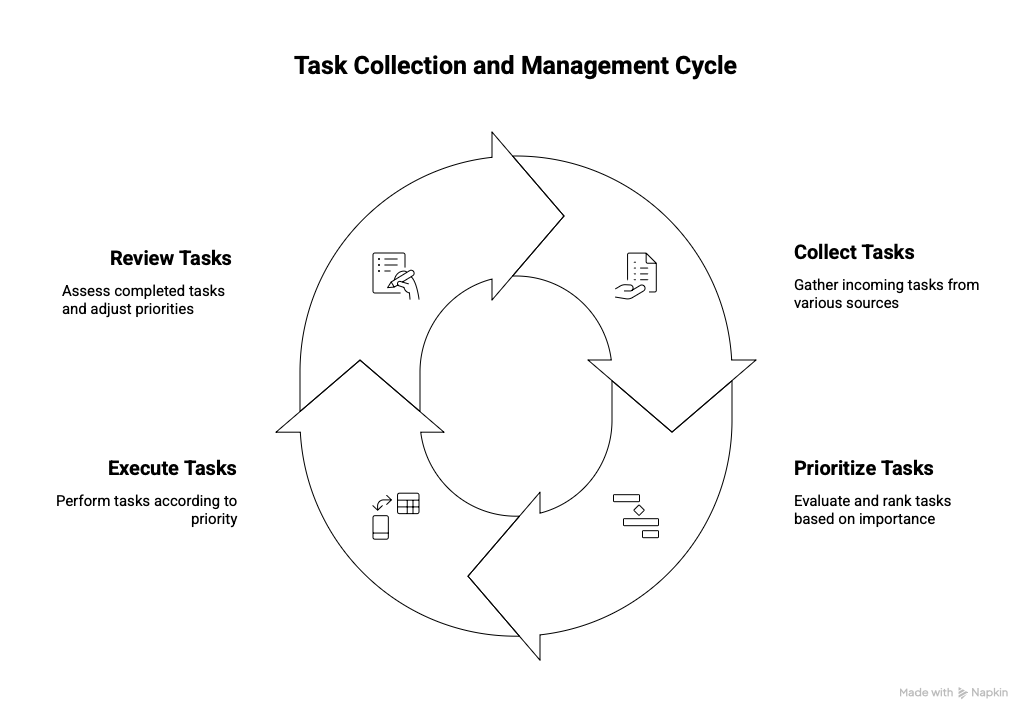

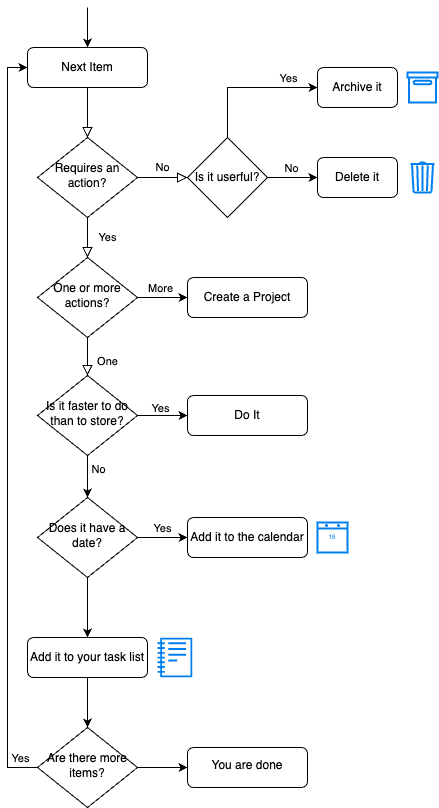

Processing

The second step, Processing your InBoxes, involves selecting which tasks are actual tasks, which ones you can complete, and which are single tasks versus projects.

The procedure involves moving each task to the correct container, allowing us to execute it as soon as possible. It is easier to follow a flow to understand than to explain it.

This is a very simple flowchart that you can expand as you become more proficient in this processing procedure.

Requires an action?

The first question we should ask ourselves is, does this item require an action for completion? If it does not require an action, it should be a piece of information rather than a task. If this information remains helpful or valuable in the future, we should consider archiving it. We’ll explore archiving information in the following chapters. If it’s not helpful or won’t be, delete it or discard it.

One or more actions?

We should consider task items that require a single action to complete, in other words, complex tasks. If we need to perform more than one task to complete this item, that is what we call a project. A project is a set of tasks that you need to perform to fulfill a need. It means that, if we can divide that item into smaller tasks, we have a project in front of us.

We are better at dividing a complex task into simpler tasks, solving them individually, and then integrating the different outputs into a single, comprehensive solution that addresses the problem.

Some examples that we can consider tasks or projects are:

- Clean my car: task

- Buy “Booster Skills” Book: task

- Plan my vacations: project

- Fix the electric installation at home: project

As you can see, the difference lies in whether there is a single or multiple actions. We can’t do our vacation planning in one chunk of work; we can divide it into:

- Get some catalogs from travel agencies

- Decide which days I will take my vacation

- Create a list of possible destinations

- Ask my family about which is their favorite destination

- etc

Once you create a project, you must treat it as a new inbox containing only the next task.

Is it faster to do it than to store it?

In his book Getting Things Done, David Allen states, “If an action takes less than two minutes, it should be done at the moment it’s defined.” This rule of thumb can help determine whether it is worth entering a task into the task management system or if it is better to complete it and never store it. My experience is that it’s never easy to evaluate whether you can do something in two minutes unless it’s a straightforward and precise task.

If you are certain, proceed with completing the task immediately. In case of uncertainty, either store it or start doing it with a two-minute deadline. If you haven’t been able to complete it within those two minutes, store it. You lose a maximum of two minutes, not a significant loss. Try to minimize this situation; two minutes is not a lot, but ten failed tasks are twenty minutes of investment.

Does it have a date?

According to GTD (Getting Things Done), tasks shouldn’t have a specific date; instead, they should be prioritized based on informed decisions. The problem is that the real world has tasks with deadlines and exact dates. The rule here is that we have a calendar for tasks that should happen on a particular date. We shouldn’t forget about the calendar as part of our task management system. It makes no sense to do a task before or after the exact time it needs to be done, so the calendar is where tasks with specific dates should be, not in our system.

Task Prioritizing

There are many ways to prioritize tasks, and you can find books on how to do so in sophisticated ways that I have yet to utilize. However, in my experience, and as I will often repeat, the most straightforward procedures are the most effective ones, and the ones you will not hesitate to use.

My favorite one is the so-called Eisenhower Matrix.

Eisenhower Matrix

When we start collecting our pending actions, tasks, or issues, the first problem to face is a fundamental question. Which is the proper order to execute all my unfinished tasks? There are many methodologies; one of the most straightforward and valuable is the Eisenhower Matrix. This method is the first filter you can apply. It will guide you on what to do first and how to follow.

The Eisenhower Matrix, also known as the Eisenhower box, is a straightforward yet effective method for classifying our pending tasks. This method’s basis is the simple principle of first attending to what is urgent and essential, and then deferring to later what is not urgent but important.

Dwight D. Eisenhower never claimed this method, but it is attributed to him because he said: “I have two kinds of problems, the urgent and the important. The urgent are not important, and the important are never urgent.”

This explanation simplifies the method, but it is a good starting point.

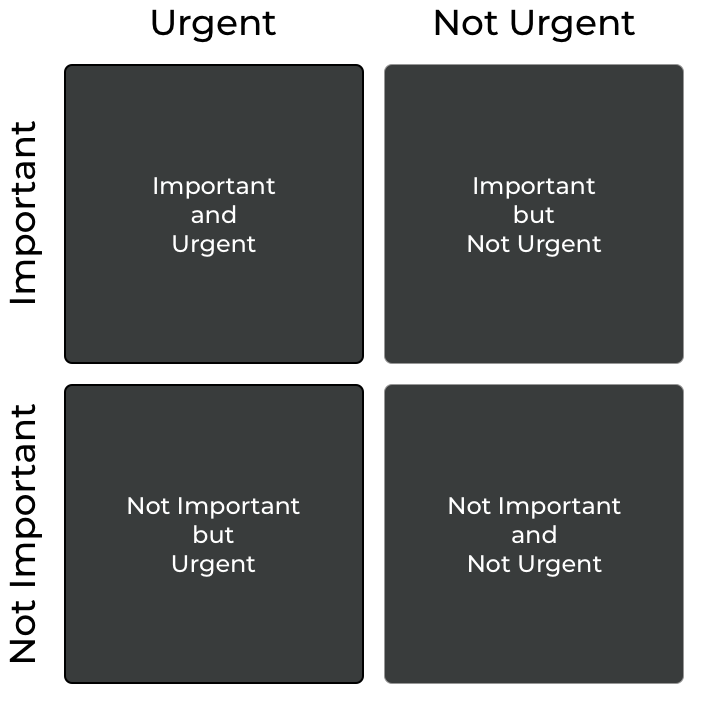

This matrix categorizes tasks into two categories: Important and Urgent. The four quadrants recognize the following categories:

TIP

Important and Urgent: Anything vital to our activity that we can’t postpone.

Important but not Urgent: We can take our time to execute those critical things.

Not Important but Urgent: Any task that we can’t postpone but won’t significantly impact our activity.

Not Important and Not Urgent: These things are not vital to us and can be delayed.

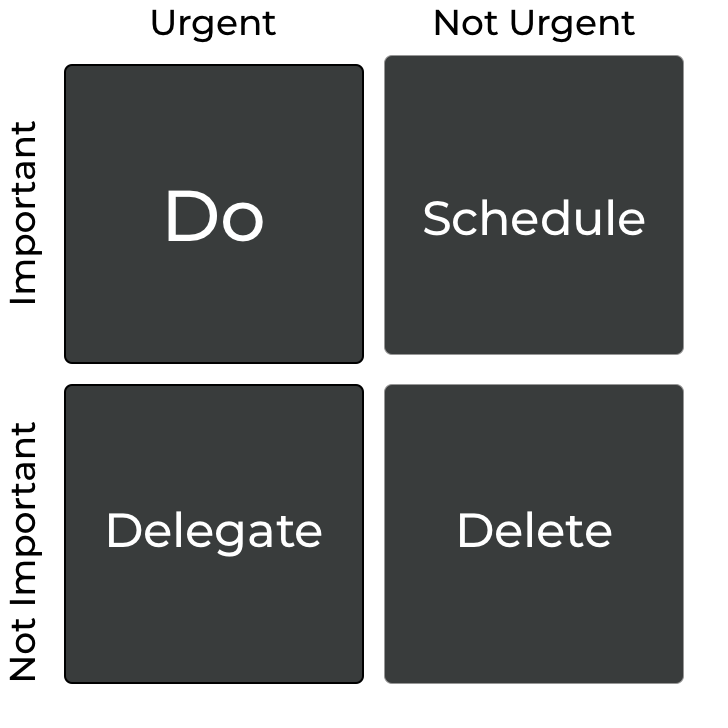

Using this classification, it becomes smooth and precise what to do with any task in one quadrant.

TIP

Important and Urgent: These are the tasks we should focus on. Any question that requires our attention and affects the work we can’t delay should be our priority.

Important but not Urgent: When we classify something as necessary, we are the person who indicated it. If we postpone it, we can schedule it and execute it at the ideal time.

Not Important but Urgent: Considering something unimportant allows us to delegate tasks to someone who can do it as soon as possible.

Not Important and not Urgent: This is the most straightforward classification to execute; if it’s not important and not urgent, delete it. We can’t spend our precious time on something that doesn’t affect us and doesn’t require us to do it soon.

By applying this methodology initially, you can eliminate many items that shouldn’t be consuming your time and delegate many to someone else who can handle them. At the same time, you get a simple sorting method that guides you on what to do and in what order.

Grouping

Sometimes efficiency can be achieved by grouping tasks meaningfully. It makes more sense to group the emails and meetings, rather than doing an email, then a meeting, switching to a meeting, and so on. As we saw in the previously, changing contexts is costly.

In addition to the priority system you decide to apply, avoiding context switching becomes particularly relevant. In this case, we should consider not only the different types of tasks but also the place, support, time, or people needed to perform the task.

Let me bring back the cost of context switching, grouping makes context switching disappear in many of the cases, so this is a very “cheap” way of improving efficiency, don’t you think so?

Examples of context can be:

Place: Your office in Barcelona, your home, the supermarket around the corner, the office in London.

Time: Morning, afternoon, evening. In this case, only if there is any constraint about the moment you can do the task or when you feel more productive or focused.

Support: Computer, phone, notebook, tablet.

People: A teammate, your boss, the designer, your couple.

Application: Mail, Browser, CMS, IDE.

The relevance here lies in the fact that when you need to do something in the office, it makes no sense to go to the office to review an email, then move to the supermarket to buy food for dinner, and then return to the office for a meeting, etc. This one is a clear case. You can see the rest in the same way. Try to group all tasks you do at the office together, then categorize them by support or people, and so on. The number of groups and their type depend on each person, circumstance, or mood. You need to make this decision, but do so in a way that minimizes context switching as much as possible.

Focus

I’ve heard many people say that they can’t focus on the same task for more than ten minutes without taking their phone, going for a coffee, checking an email, or engaging in any other distraction they can think of. When they tell me so, I always ask the same question.

Can you go to a theater to watch a movie?

Usually, the answer is yes. Then I continue.

Do you put your phone in silent mode?

Again, the most common answer is yes or “I select plane mode.”

If you can attend a movie theater and spend more than one hour with no distraction focused on a screen, why can’t you spend fifteen minutes focused on a task at work with no distraction?

The answer is straightforward; you can do it because watching a movie is a pleasant time in which you decide to spend your time. While the task is usually unpleasant, and you did not choose to do it, you must do it.

So the key is not that you can’t. The key is that you don’t want to; that’s when procrastination appears.

If you want to avoid procrastination, there are excellent techniques you can apply, and that is very clear in the book Eat that Frog by Brian Tracy.

Start with those tasks that you like less or have more difficulty with.

We all prefer some tasks over others. If you have to do them all, start with those that are more challenging for you. The sooner you finish them, the sooner you are free to do more pleasant ones. We are usually more active in the morning, as we have not yet consumed our energy. That is the moment to go for it when your energy and activity levels are higher, as you are more vital; your power to overcome the intention to procrastinate will help you finish it and move on to another, more pleasant task.

Don’t waste time thinking about how to perform that task. Start as soon as possible, and you will realize how to do it.

Martin Luther King Jr. once said, “Take the first step in faith. You don’t have to see the whole staircase; take the first step.” This means that it is not necessary to have the whole plan done and the complete procedure straightforward to do anything; you need to start, and as you go, you will see the next step. The opposite would end in what is called paralysis by analysis. You spend most of your time analyzing how to do something, but you never actually do it. Remember that “The perfect is the enemy of good”.

It doesn’t matter how much you work. The final goal is the delivery.

You can work as hard as the next man, but you must finish the task and deliver to succeed. Prioritize and deliver. Group and deliver. Complete your current task before beginning the next one.

Focusing on a task is crucial to advance. The task you are working on has to be the most important thing for you in the following minutes or hours. Never leave a task incomplete; if you have no time to finish it, move it to the next day’s to-do list first thing.

Takeovers

TIP

We can only do one thing simultaneously; what we perceive as multitasking is task-switching.

Not all tasks require the same level of attention. Only simple tasks that you have practiced for years can become background tasks.

The cost of the minor interruptions can have a significant impact on our delivery capacity.

A system like Pomodoro can help us focus for the maximum time possible while avoiding interruptions and fatigue.

Knowing the stage we are at helps us understand the required effort and the level of expertise we aim to achieve in a specific skill.

Following a specific framework, as presented in the flow chart, will help us clarify what we should focus on at any given time in our work.

When everything is important, nothing is. We must set priorities for every task we need to work on.

Group tasks by context, which will help avoid context switching and significantly impact your performance.

Focus on the task you are working on at any moment; that is the most important thing you must do, and don’t stop until you finish it.